THE HEAT CHECK: HALL OF FLOWERS 2023

THE HEAT CHECK: HALL OF FLOWERS 2023 We hit Hall of Flowers to see who had the heat! One of our absolute favorite activities here at L.A. Weekly is to see the heat of the moment at major cannabis events. There are few places better to do it than Hall of Flowers as the industry…

THE HEAT CHECK: HALL OF FLOWERS 2023

We hit Hall of Flowers to see who had the heat!

One of our absolute favorite activities here at L.A. Weekly is to see the heat of the moment at major cannabis events. There are few places better to do it than Hall of Flowers as the industry gathers to grade the current product on the market.

As one might expect, the show and tell can get serious quickly. Here are some of our favorite finds from Hall of Flowers.

Fresh Powerzzzup Terps

One of the cool things about running into the Powerzzzup team is getting the chance to check out various renditions of their gear. As we noted in our feature article on Powerzzzup in 2021, lots of different farms across the country run their genetics. On this occasion, we got to see some 2090 Shit grown out veganically by the team at Feeling Frosty Hash. It was savage heat that tastes awesome but has a strong impact. f.

CAD Nana’s Ultimate Greaze

Carter’s Aromatherapy Design is at it again with one of the heaviest-hitting topicals on the recreational market. Nana’s Ultimate Greaze features 1000 milligrams of THC and 500 milligrams of CBD. This is probably a lot more potent than whatever topical you’re using if you’ve ever felt the urge to up the strength a bit more.

Bruno is Back in America!

Following his recent adventures to the Canary Islands to judge The Canary Islands Champions Cup, Bruno is back in California rolling some of the best prerolls in the game with some of the best material available. On this occasion, Bruno was rolling up prerolls at the CAM booth for the buyers on hand to try CAM’s wide range of flavors.

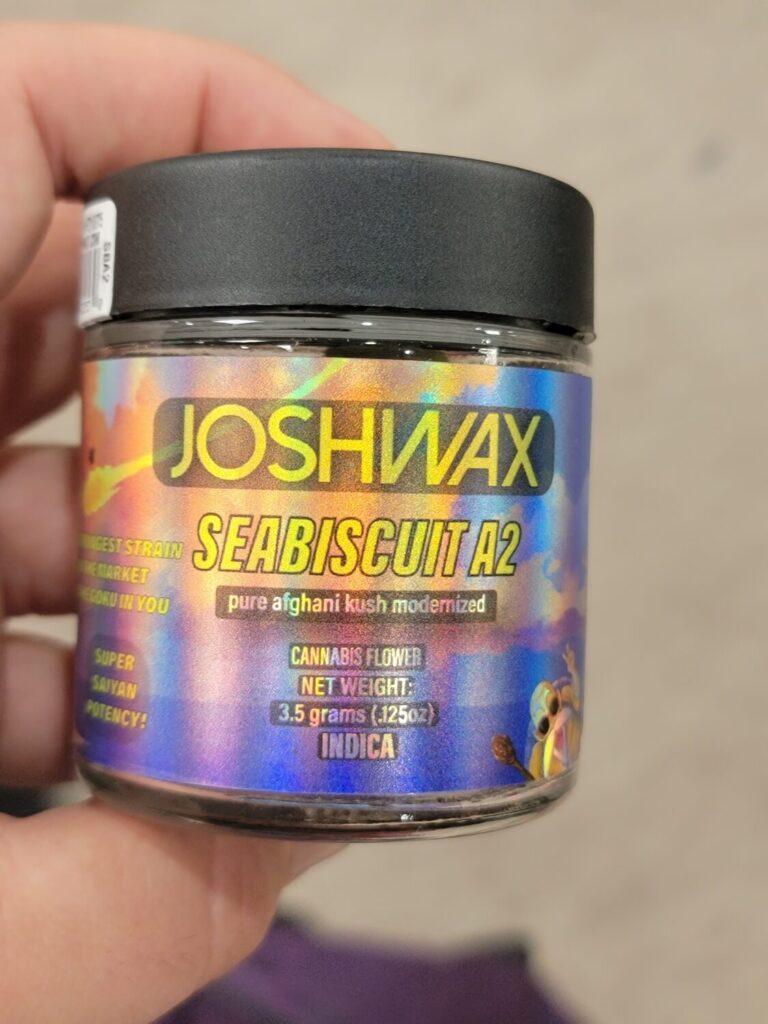

Joshwax Seabiscuit A2

While many of the big-name companies reminded us of why you hear their names a lot, Joshwax was someone who had to have their stock go up following Hall of Flowers. It’s not that Joshwax didn’t have good pot before last week, we just found the kushiness of the Seabiscuit to be something really special.

Masonic Seed Co x Fiore

The team at Fiore drops a lot of heat, but the Banana God is being grown in collaboration with Masonic Smoker is right at the top. You can taste all the flavor notes that have seen a lot of hardware added to Banana God’s trophy shelf over the last few months.

Dueling Strains

SF Canna’s new two-packs featuring two eighths is one of our favorite new offerings from anyone at Hall of Flowers. There is a QR Code on the back so you can score your favorites after and help the organizers find their winner.

Art courtesy of The Freak Brothers

Art courtesy of The Freak Brothers